Often, the idea of illusion is present in the conceptualization or realization of my work. But the invitation by Jorge Daniel Veneciano to contribute to his special edition of ART21 Magazine prompted me to rethink and re-see some of my work more expressly within the framework of illusion.

In a sense, all of the arts, especially the visual arts, are composed as simulacra. Hence they are, in effect, illusions. With this framework in mind, one finds that the phrase, “What you see is what you get,” doesn’t apply to the arts: what you see is never exactly what you get. What you get, instead, is an illusory effect.

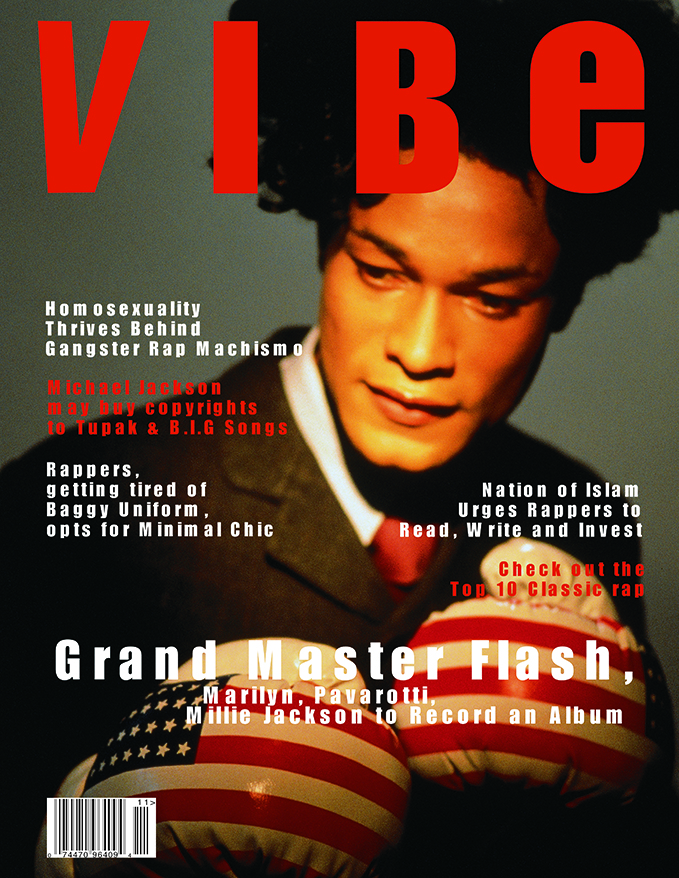

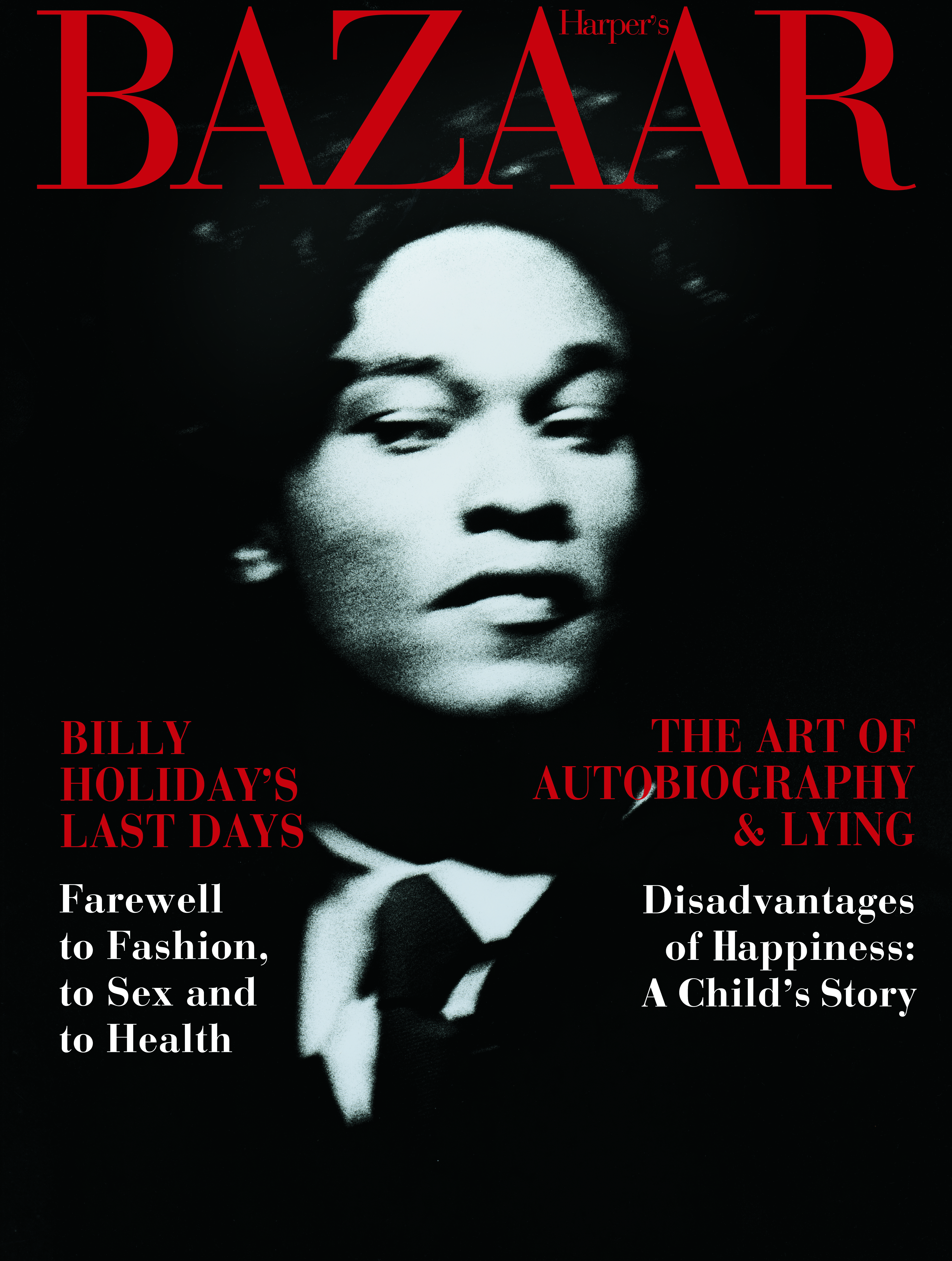

For instance, in my 1994 series, Cover Girl, my original concept was a critique of the politics of magazine covers: their simultaneous mass representation and under-representation of faces both imaginable and unimaginable. Viewing this body of work in retrospect, I see the series as an embodiment of illusion. In it, I designed magazine covers as deceptive simulacra of various well-known magazines—including Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, GQ, Newsweek, and Glamour as well as now-defunct publications, such as The Face, Vibe, Arena, and Mirabella. My covers confused viewers then, and still do, because they were believable: they look and feel like real media products, and so are often mistaken for the real thing. They were deceptive in that sense, designed to convincingly engender the impression of reality in the world of media.

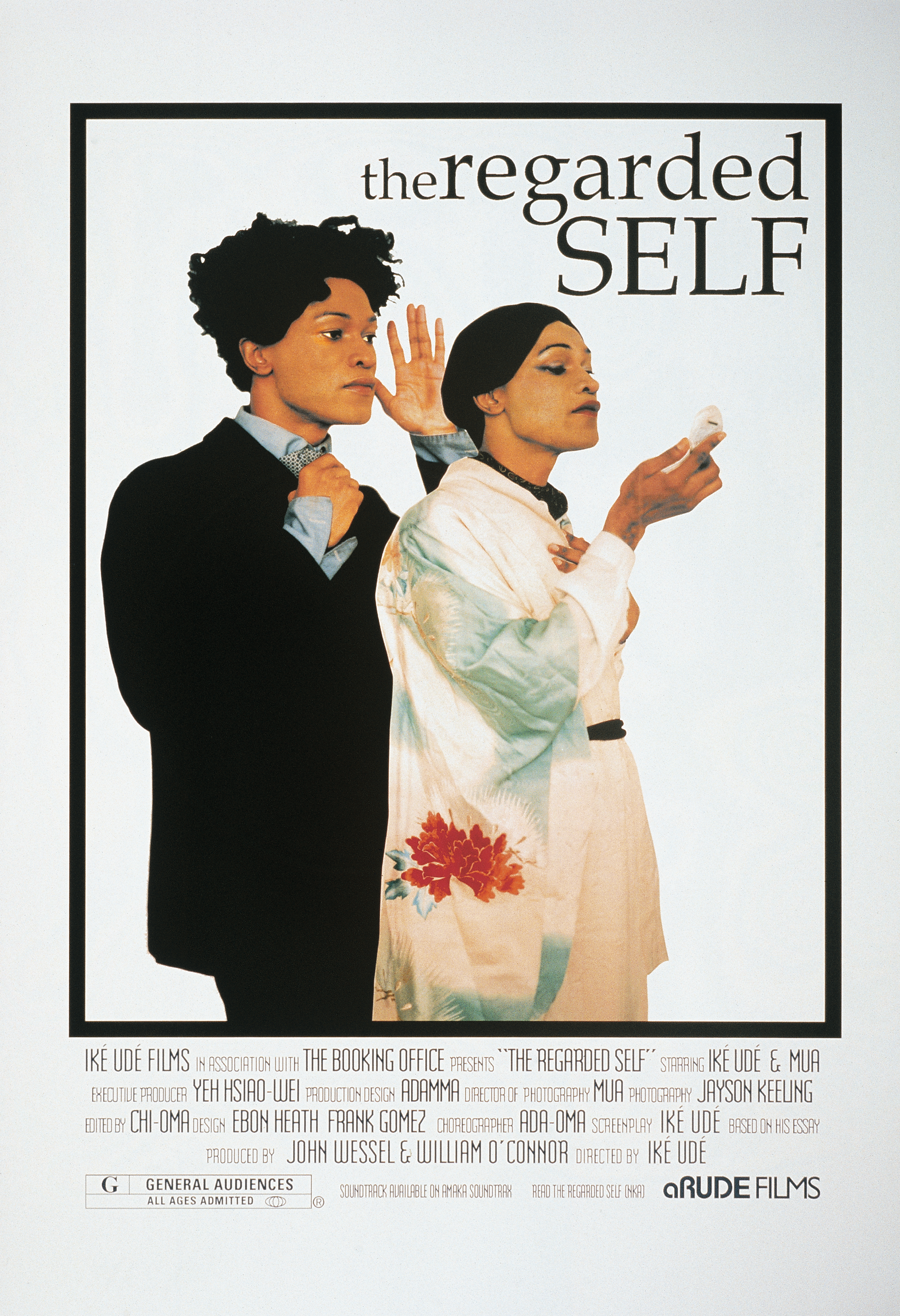

The same illusion is obtained in my 1995 series, The Regarded Self, in which I made simulacra of movie posters. I wanted viewers to perceive them as posters of actual motion pictures. With The Regarded Self, what particularly appealed to me was its economy of conceptually making a movie: to use the movie poster as a shorthand method for envisioning a wildly imaginative, open-ended, and not-yet-feature film. I rarely see more than five percent of the movies advertised through posters, yet I have a one-hundred-percent recall of these posters and can create my own narrative of the movies without ever seeing them. So, for me, the illusory effect of the movie poster was enough to conjure the unseen actual movie.

This tension between reality and illusion is at the heart of both the Cover Girl and The Regarded Self series. Things are not always what they seem. And often, in life as in art—and especially in most of my work—this rule is nearly a constant.

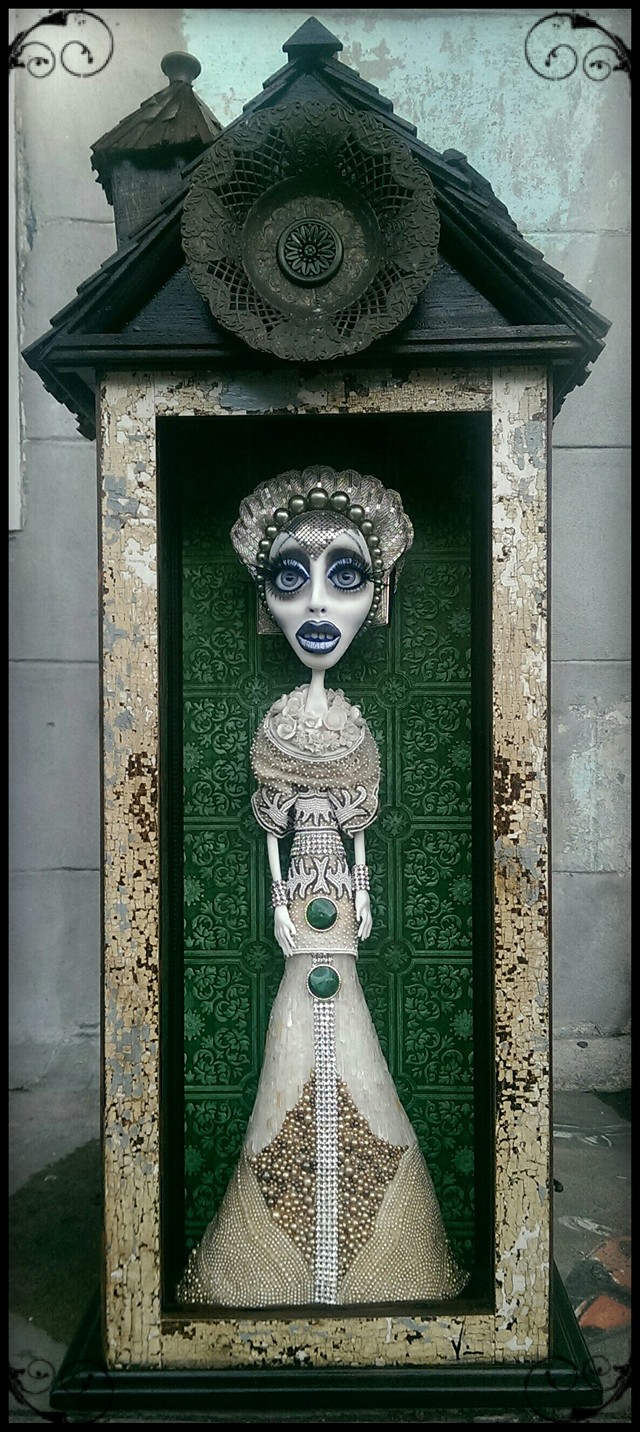

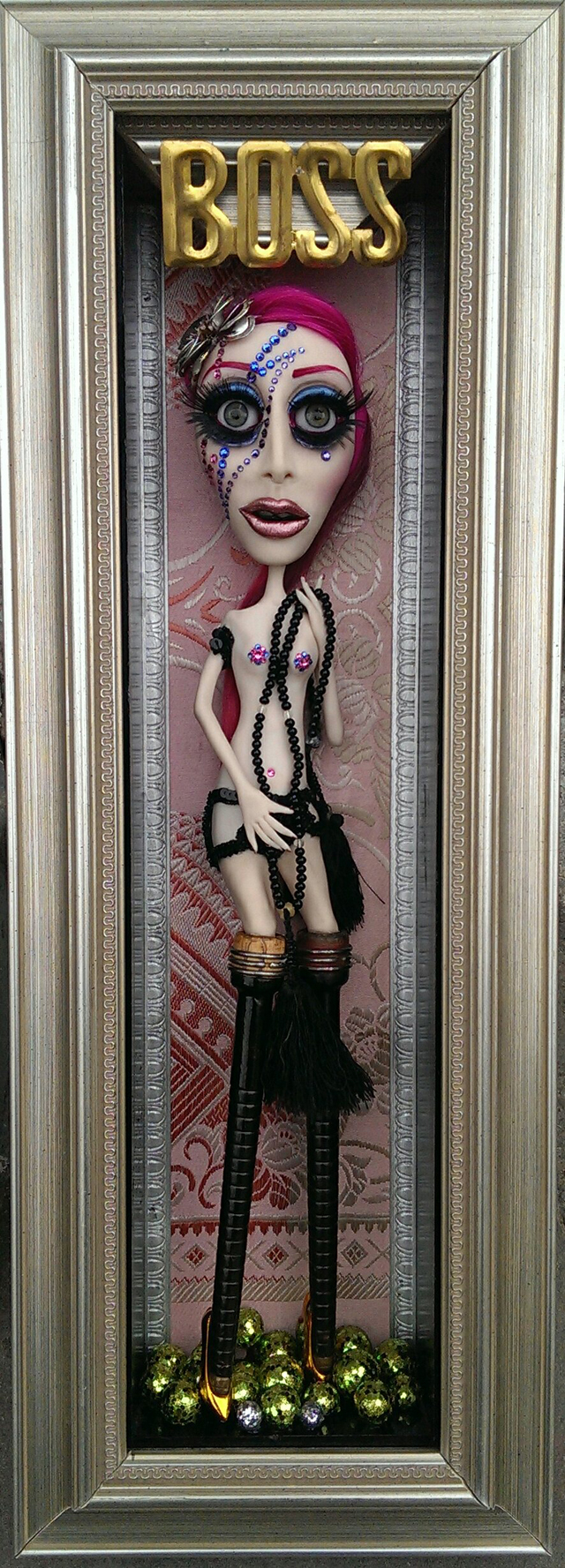

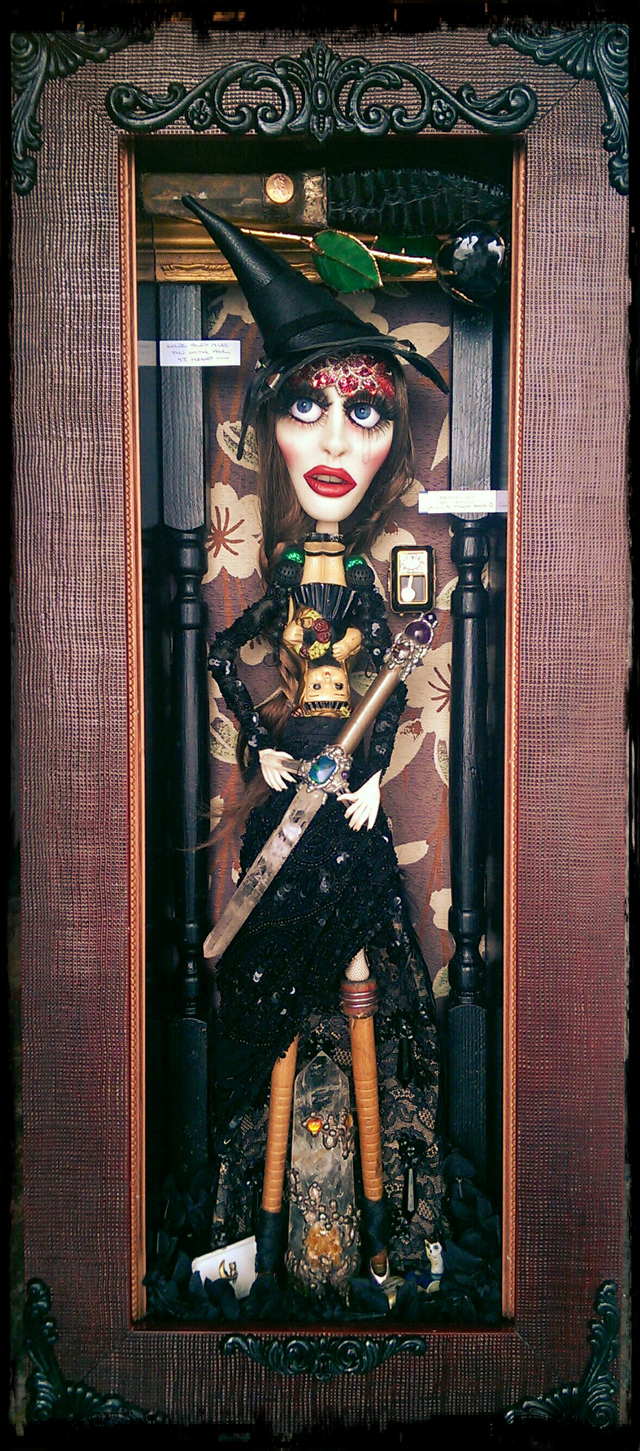

Sartorial Anarchy is a more recent, ongoing body of work that I began in 2010. In it, I explore the sartorial ciphers of representation and identity as agencies of illusion. These markers of representation are in constant flux, not fixed; they are negotiable, permeable, and mixable. They are exquisitely multilayered in organization.

Take, for instance, Sartorial Anarchy #5. It’s a veritable United Nations equivalent of costumes, but across time, as well. The work quotes from varied costumes and from varied cultures and periods; it’s important to account for these details. Sartorial Anarchy #5 is composed of: a miniature fedora, 1920s; a macaroni wig, England, 1850s; a fighting stick, Zulu (South Africa), 1950s; a Norfolk jacket, 1859/60–present; a miniature blue/silver vintage brooch of a Philadelphia policeman, 1940s; a two-tone, white-and-blue collar shirt with French cuffs, 2009; canvas boot spats, World War I era; dress shoes, Yoruba, Nigeria, 1970s; an antique chair, origin unknown, 1940s; a gladiolus plant; a vintage side table, origin unknown; an antique blue gabbeh rug, Persia/Iran, 1900s–30s.

Mixed in multiple layers, the various ciphers of costume and fashion—which originally represented different cultures and geographies—have been effectively dislocated, relocated, refashioned (as it were), and reorganized to create something new, irrespective of their original meanings or assignations. In this work, I created a fashion field without borders: a sartorial anarchy. The resulting composition obtains the illusion of coherence, but upon closer examination, one finds that the sartorial elements employed do not necessarily belong or ought to belong together. Nonetheless, the ensembles work. In this tension, there is an order of illusion, produced by the illusion of order, and this is an essential play that motivates my work.

Iké Udé. Sartorial Anarchy #30, 2013. Pigment on satin paper, 45.7 x 36.5 in. Courtesy of the artist.

Iké Udé’s latest series, Nollywood Portraits: A Radical Beauty, will be on view at the Museum of Contemporary Photography at Columbia College Chicago October 20 — December 23, 2016.